We land after sunset and drive two hours out of the city – into the Andes – into the darkness. Half of us fell asleep in the van, and woke up in front of the guard entrance of ALMA – the Atacama Large Millimeter Array. We walk into a cinderblock building with a small office in the corner. There are 10 folding seats against a wall facing a TV. As we sit, A golden retriever trots up to Laura-May. ALMA has a pet dog named Almito. One day, after a storm, he showed up in front of the guard station, a puppy, all alone. The observatory takes care of him. Almito is old; he recently had a part of his nose removed, but is otherwise healthy for his age. He’s famous on instagram – an essential part of the observatory’s social media campaign. “This guy probably has better healthcare than the average US citizen.” We’re drowsy. We watch the safety video and give pets to Almito.

ALMA is an array of 66 radio telescopes that work in unison. Each telescope weighs 100 tons, but they do not sit on permanent foundations; they can be moved by transporter truck to modify the telescope. When the dishes are close together, they have a wide field of view. When the telescopes are moved far apart, they zoom in. The signals from each of the telescopes are synchronized and combined using a supercomputer, also at the mountaintop.

ALMA has a residence at 2.900 meters, where the staff live and work, and a high site, at 5.000, where the Antennas live. At the top, oxygen is required at all times. The elevation of the low station is higher than the summits at Cerro Tololo. Stronger safety precautions are required. One of the guards presents us with a large handheld device and asks us each to press it. There’s a big yellow button on to that beeps red or green when we press it. When it beeps red, you’ve been selected for a random alcohol screening There would be no Pisco Sours until we left. Yasmin fills out some paperwork for us, and then we’re on our way.

Most of us drift into sleep again and wake up 15 minutes later in front of La Residencia. We walk through the glass doors, up to the mess hall, and eat our pre-packed meals that the canteen cooked for us. We’re all feeling the altitude in different ways. We go to bed.

Sleep is fitful with thinner air.

We wake up.

It’s the middle of the desert.

Outside, a Martian landscape stretches for hundreds of kilometers. The Andes mountains in the distance look like anthills. Streaks of rust brown, white salt flats, and flecks of green stretch across the plain.

Now that I’ve had some rest, I look around, both at my room and the facility. Scanning my room, I realize that I’m in fact staying at a luxury hotel. The bed is soft, white and comfortable. Across from the bed stands a wall-length desk and a sofa chair. On top of the desk is a personal blue water cooler, with a spare 50 liter tank underneath. The lighting is soft, varied, and directional with a control panel near the bed. Blackout curtains can block out even aggressive Atacama sunrays – when closed, one has no idea where they really are. I move to the bathroom – it’s large and bright, with plenty of room for employees to comfortably live. There is one single clue that I’m not staying at a Mariott – a sign on the shower door, pleading with me that water is scarce – please shower as quickly as possible.

I dress myself, then check my watch. I’m shocked! It took me 45 minutes to put clothes on! How is that possible? Am I disoriented from the lack of oxygen?

I lock the door to my room, it’s solid wood, maybe cedar, 3 meters high. The hallways continue the illusion that we’re staying at a luxury hotel. Walking outside, differences now arise. The morning air is cool and dry. The exterior architecture is thoughtful, with color tones that match the environs. The intention of the design is to “blend into its surroundings”.

A concrete path leads to the main common area. Behind the dormitories are the warehouses, generators, and laboratories. Dirt roads wind around to reach each area. Foot sized stones line the roads – delineating the razor thin boundary between untamed nature.

You can check out more pictures here.

We meet again in the same canteen for breakfast. Now that we can view outside the windows, reality sets in about where we are. We’re served buffet breakfast and eggs, totally isolated from the rest of the world. The only scientific station more remote than this one is the South Pole Telescope. We’ve been told they may have a surprise for us today.

Breakfast concludes, and we return our meal trays back to the serving counter. Down the hallway, we pass a huge shelf of sports trophies.

“What are those?”

“Those are from the interobservatory games. Every year ALMA competes with other observatories in Chile.”

In 2016, ALMA finished first in volleyball, chess, and tennis; second in hopscotch, dominoes, and pool; and third in soccer, basketball, and ping-pong.

“Why do you have so many trophies…. is it because everyone here trains at high altitude?”

Imagine the conditions that these people work in. The nearest town is more than 2 hours away, work is intense and around the clock. They must stay here, work in shifts, at high altitude, 6 days on, 8 days off, 11 hours a day. Staff must clear a medical check every time they go to the high site. Blood pressure and heart rate must be normal. This can be challenging for visitors, who are not used to the conditions, and are also nervous they could miss their once in a lifetime chance to see the dishes up close.

As new arrivals, they caution us to even go slowly up the stairs. Don’t drink coffee. The body’s endurance is massively depleted with 80% oxygen. Is exercise alone a safety risk? Not necessarily. Most people are able to acclimate after time to higher altitude. Their bones produce more red blood cells to become more efficient at absorbing oxygen. That’s exactly why doping works. With adaptation, one can even train. Employees need something to do with their free time, so gym facilities are provided. The National Science Foundation even built recently a football court, partially underground so that it remains cool in the heat of the desert. That’s the dome I saw earlier. The operators of the telescope array, the people who enable us to study the Universe with radio waves – they are in top physical and mental condition.

I repeat – altitude is harsh on the body. Some people get a bad headache. Others turn in their stomach. I experienced loss of judgment.

Exercise is good for your blood pressure, no?

So after breakfast, before we tour the offices, I walk back to my room to change into gym clothes. On my way down the metal staircase, I pass a sign sticking out of the gravel:

Silence!

Day sleepers!

What strikes me about these remote research facilities is the silence. There are no birds chirping. No whishing of car traffic. One hears only the lonely drone of generators in the distance. The sun makes no noise as it shines down on my face. With less water vapor between us and the sun’s ultraviolet waves, it’s possible to get burnt through one’s clothes. I wear my shadehat even for the short passage between buildings.

Passing back through the common area, I swing a right, past the laundry room, and then into a changing room. Disoriented still, it takes an alarming amount of time for me to stow my belongings in the locker. This disorientation, it’s hard to describe. When you have a headache or a hangover, you feel pain. You feel out of it. This was something different. I felt normal, except that I was absentminded, oblivious and less intelligent. Mistakes are easier. How do people operate heavy machinery up here?

I push on the door from the locker room into the sports facility. I smell chlorine. In front of me is a single swimming lane, pristine. To the side of it is a Sauna. There’s a sauna in the middle of the desert. Going to the Sauna is a special tradition in Denmark, where I live. It’s simply a part of life. I read the instructions, but I’m unable to start the furnace. I decide to walk away, take it easy. But I would become fixated on using the Sauna.

I walk to the other side of the pool, where there’s a treadmill and some weight lifting equipment. I stretch, as I normally would. I try a few pullups. 1,2,3…..4……..5…… it feels like I just did 50. Then I move to the treadmill. I set it to a fast walk and get moving. After 15 minutes, I’m totally out of breath. I’m pouring sweat. Somehow, that took me an hour. Time to get ready for the day.

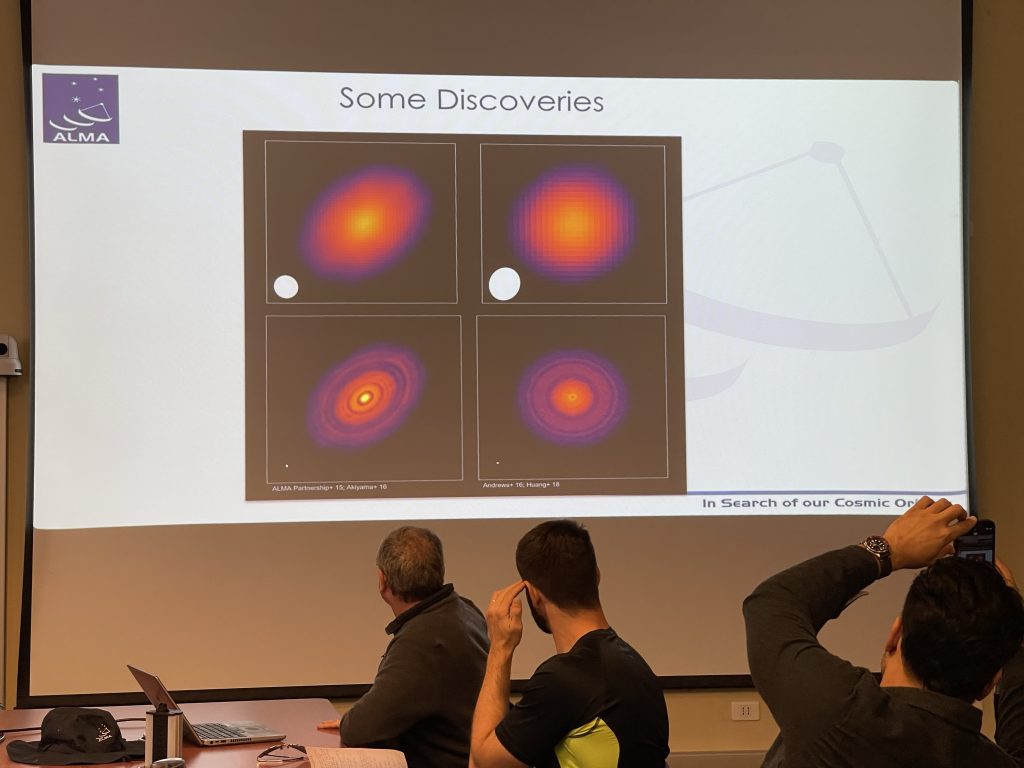

Have you ever wondered how the solar system formed? How did it look, 4 billion years ago when the sun had just ignited? How does floating around a star like a ring – turn into planets? ALMA famously studies protoplanetary disks – baby solar systems. Because of their warm temperatures – around 700 Celsius – we can study the with radio waves. That’s what’s meant by Atacama Large Millimeter Array. The wavelength of these radio waves are about a millimeter long.

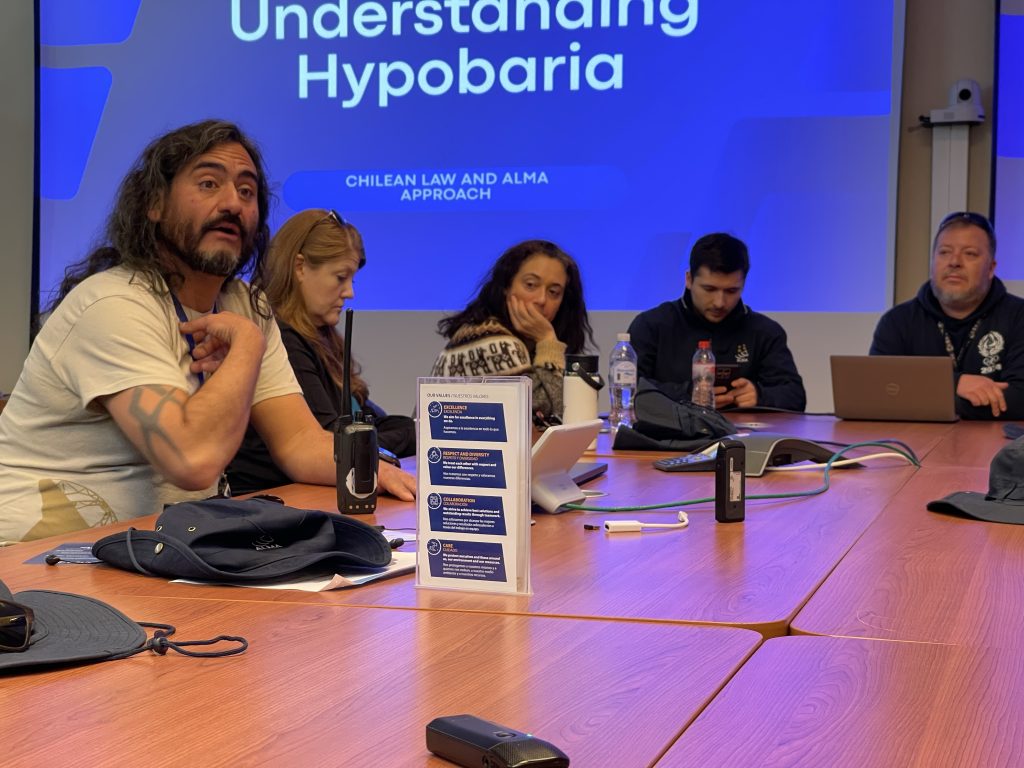

We’re sitting with a panel of four staff members who took time aside to meet us and explain what daily operations are like at ALMA.

Have any of you looked through a hydrogen alpha telescope before?

All four, hesitant, nod no

“It’s a special instrument that allows us to view the sun, I would like to show you as a way of saying thanks for hosting us”

We offer to set up the telescope after lunch

There are actually few astronomers on site. During Covid, the control room was moved to Santiago. Astronomers might visit the high site once or twice in their career, for curiosity’s sake. After covid, there are no more astronomers working on site. They are all stationed at the HQ back in Santiago, operating the antennas remotely.

It was not always that way. ALMA was never meant to be turned off, it was designed for 24 hour continuous operation. When they switched the systems back on remote from Santiago, there were some doubts about it would work. Fortunately, everyone working on this project is very good what they do, and they were able to observe that first night.

In fact, the staff and skills found at the ALMA site is more like a mining company than an academic institution. There are 250 employees, 40 PhDs, 64 engineers and 83 technicians. What is needed, in the middle of the desert, are not people who can crunch numbers about the cosmos. What is needed, is a focused, handy group of people who can operate sophisticated equipment in harsh, remote conditions.

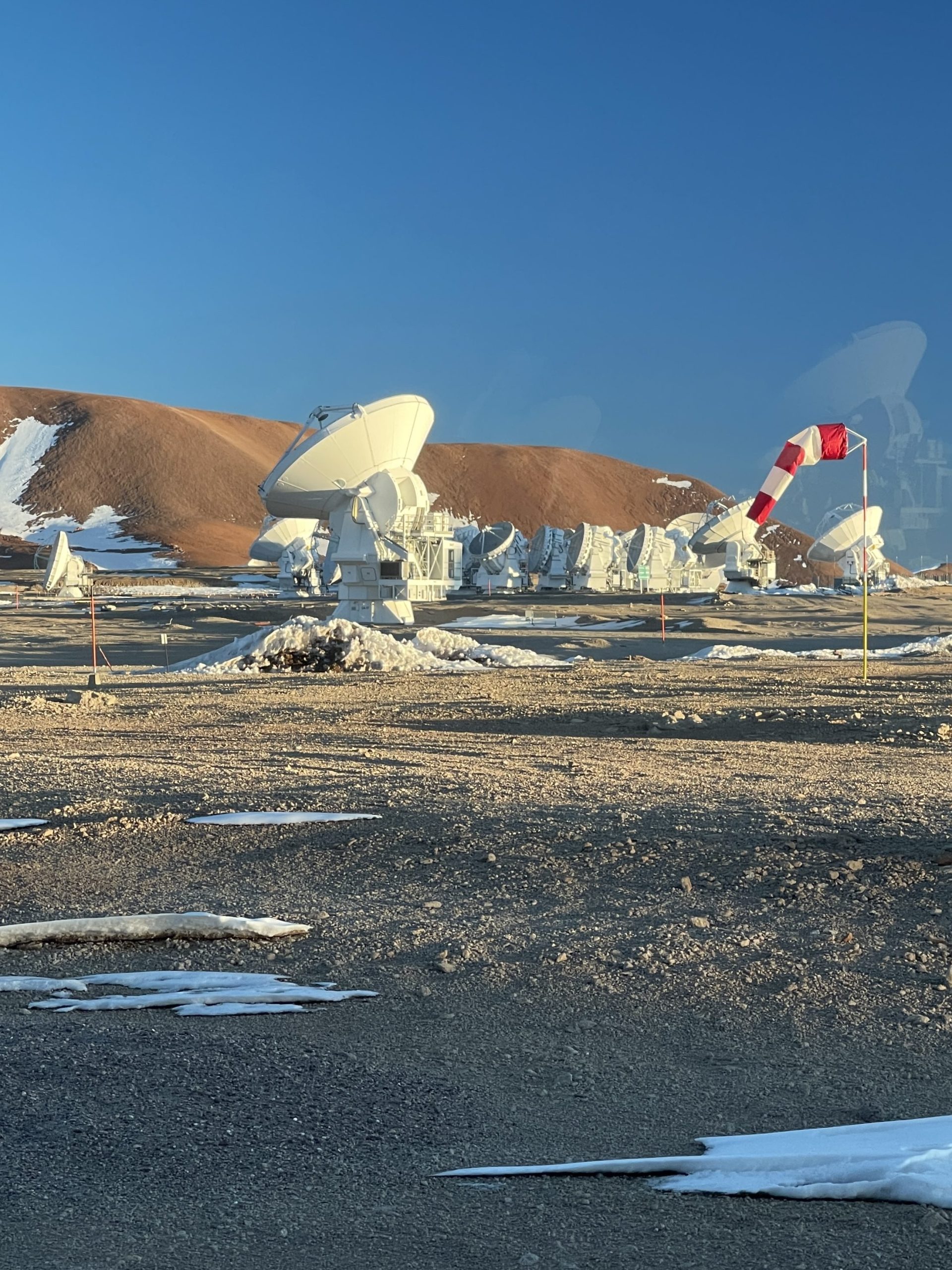

“Last week we had a snow storm at the high site. You may have read in the news that the antennas are in survival mode. What does that mean?” During a storm you have to deal with high winds and snowfall. When the wind is blowing, we turn the antennas so that they face east, away from the wind. The wind, snow and dust pushes blows around the curvature of the dish. When the storm is over, they need to melt the snow, but they don’t let workers go up there with shovels. The surface of the dish is better not touched, especially in the center, where the receiver sits. Instead, they rely on sunlight to melt the snow. The second part of survival mode is tilting the telescopes to track the sun.

There’s still a lot, a lot of work to clear the 20 kilometer long road to the high site, along with the other service roads leading to partner facilities.

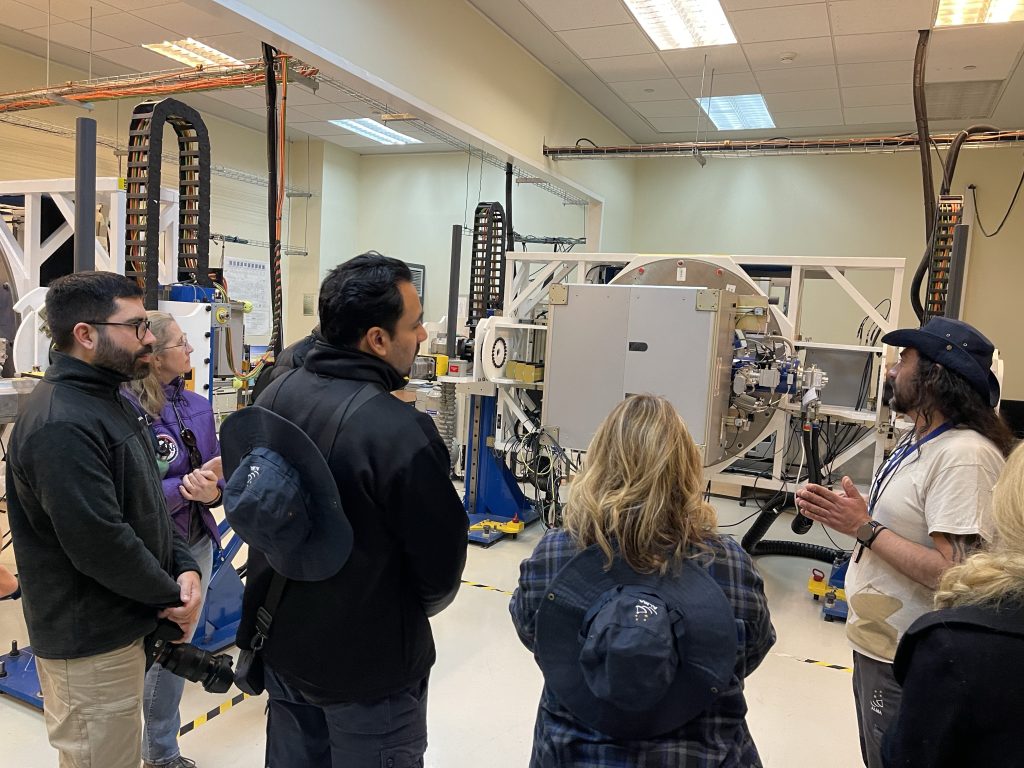

Danilo is a perfect example of what it takes to work here. Gleeful attitude, captivating story about every aspect of the observatory’s operations. Grit. He knows what it takes to survive in the mountains, and he knows what it takes to make this facility run smoothly.

Danilo shares a bit about himself. He has a long messy black beard, a bronze tan, and a few tattoos. He’s a former professional mountain climber, leading expeditions and search-and-rescue in the Andes. He lives in the nearby town of San Pedro – 90 minutes north on the highway. Because of his “proximity”, he works a modified shift: 4 days on, 3 days off.

“I’m sleepy”

“Whats your shift like today?”

“Well,I took a break between 4 and 7”

It’s noon. So I ask..

“In the morning?”

“If this place resembles running a mining company, why don’t experienced miners want to work here?” Mining conditions are extremely harsh, they live shorter lives. They are already used to shift work. He explained about the culture here. “People live longer at ALMA.” Managers know their names. We sit with each other at lunch, supervisors and staff together. At the mine, There might be one dining and accommodation for the upper management, another for the supervisors, and even a third for the laborers. People come to work here and managers know their names. People work 15 years at the mining company and the managers don’t call them by name.

“Why work there?”

“The pay is double, maybe even better.”

more notes from this conversation in your notebook.

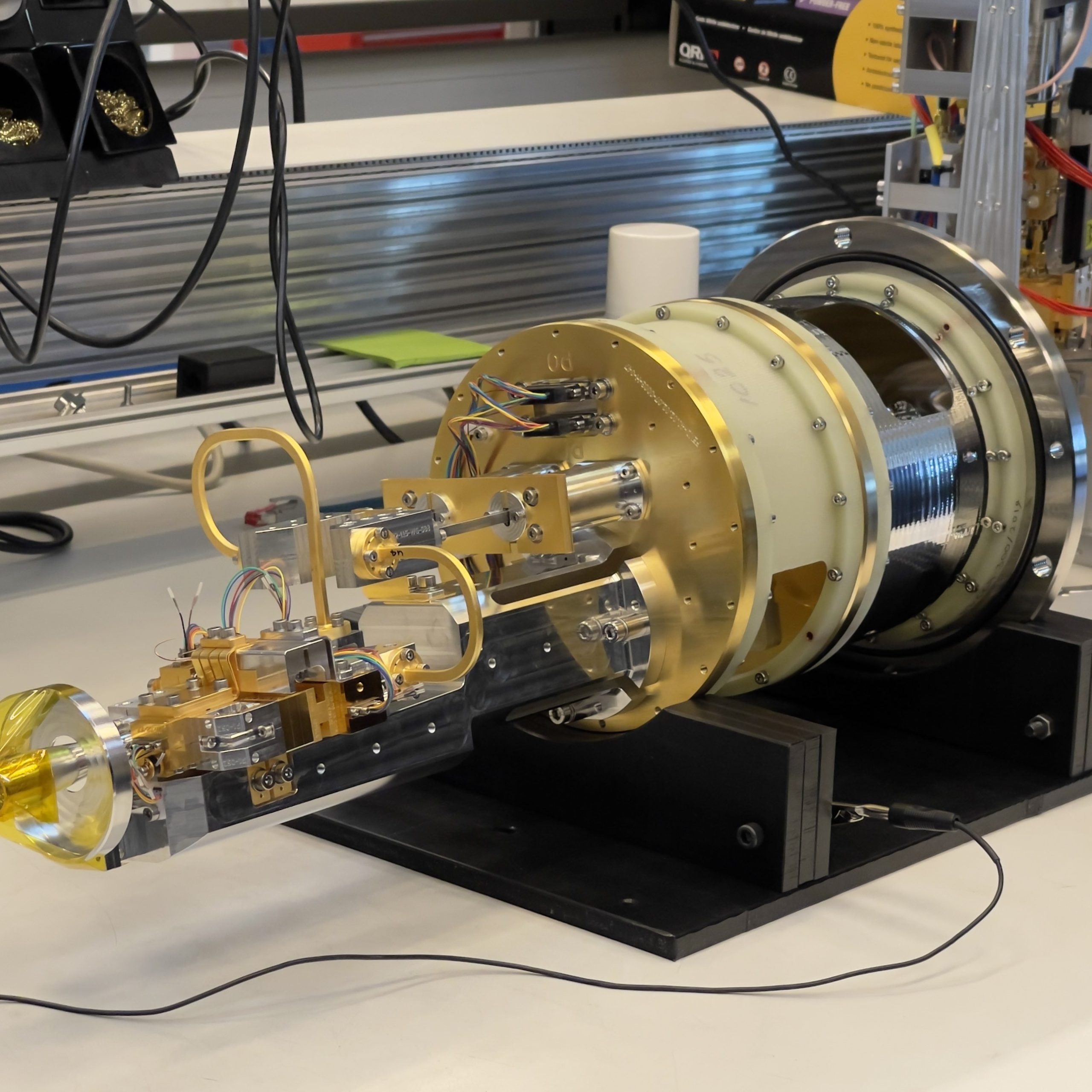

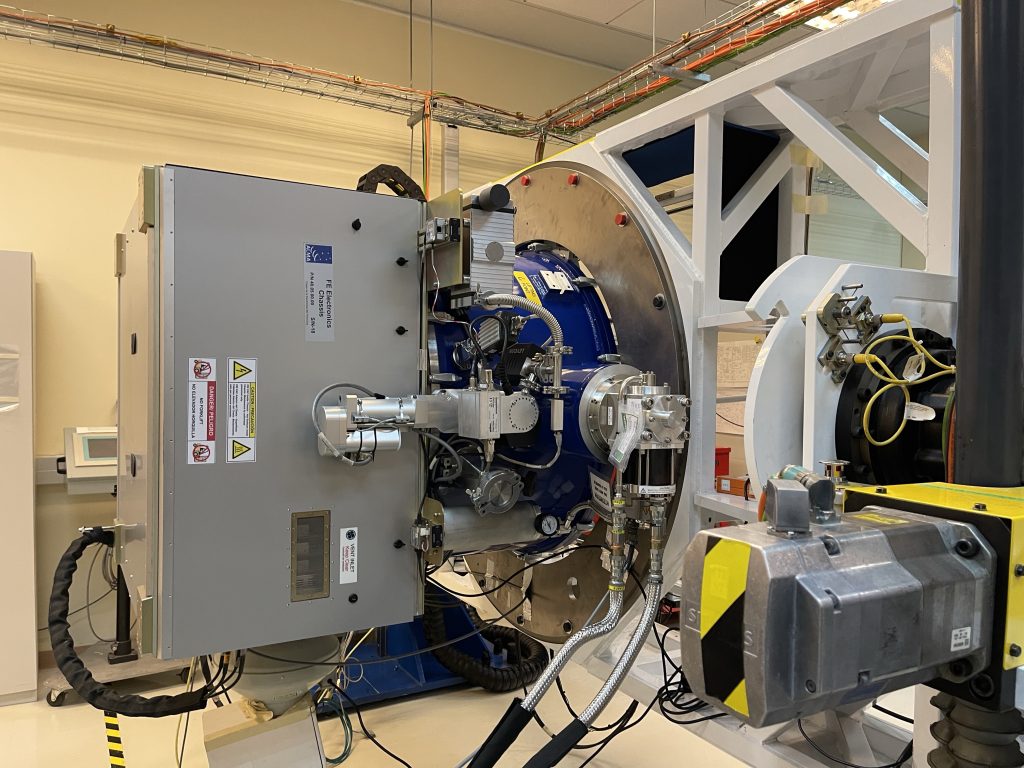

Danilo leads us down a hallway. He approaches a double door with a yellow sign on it: ATTENTION, ESD Protected area. Before he lets us inside, he warns us not to touch anything. The lab is filled with one of a kind electronics, and they are so sensitive that they are fried by the static electricity stored in our bodies. ESD: Electrostatic Discharge. Even if you don’t feel a zap, the equipment does. In fact, static shocks can give up to 5000 Volts! The total energy is low, so you don’t feel it, but a microscopic transistor, designed to operate at 1 Volt, is toast forever. We don’t want to do to the experimental sensors sitting on the bench.

This is where they repair and upgrade the telescopes’ sensors – the ones the collect the signal focused by the dish. A sonic churring fills the room. This rhythm is the heartbeat of special refrigerator pumps. Instead of normal refrigerant fluid, these pumps use liquid helium, and they can cool down to 4 degrees above absolute zero. The cold temperature helps the telescopes detect faint, cold objects. Danilo explains with precision the pumps’ principle of operation.

We leave the lab, and walk out of the offices into the cars again. At each of the buildings’ entrances, there are liter-sized SPF 50 sunscreen bottles screwed to the wall. I take a dose and apply it to my face and ears.

The car coasts around the office building, kicking up 20 meters of dust behind it. We turn the corner at the end, and now we see our first antenna of the trip. It’s sitting in the parking lot next to a hangar sized warehouse, tall enough to fit it. “Is that one waiting for repair?”

“Is that waiting for repair?”

No, it’s the first dish, one made by the Japanese. The partner countries competed to see who could deliver an antenna first. This was the first to get here, but there was a design flaw. The team decided to start from scratch instead of repair this one. United states delivered the next dish, and the first to be operational.

The antenna was never used, never listened to the sky. And it took a LOT of effort to get it here – the pieces were brought in on truck from Santiago. Now it lives in the parking lot – no point in bringing it anywhere else.

Over lunch, news of the surprise gets out. We’re going to high site today as well. Our medical checks are at 2:30. IS there time to take out the telescope, and check the sauna? Lunch passes with me defending myself, trying to convince people that saunas are in fact, good for your blood pressure. Don’t risk it Bill, you don’t want to strain yourself before your medical clearance. Yasmin seems concerned that I’ve also convinced Fefo this is a nice idea. I pass again by the fitness center. No there’s an out of order sign over the door. It seems that it was disused, and I was the first in some time to pass interest in it. I tried too hard to make it happen. I would not go to the ALMA sauna, not this time.

But there was still about an hour to spare for astronomy with the staff. Maria Fernanda picks me up and we drive back to the office building. We pick a spot outside, next to the break area. There’s sunscreen at the doorway, I apply some more. Then we step outside.

First two or three come out. Then more.

Then the word spreads though the building, at one point we have 15 people with us. Upper management comes out as well, so the staff sees that its ok to take some time away from work to enjoy the moment. “Quieres ver el sol?”, I’m getting more comfortable with this one phrase. I even add in, “Feugo!”. Early on, one of the staff jumps in and provides an intelligent explanation of what’s going on – the flames on the edge are solar prominences, they’re the magnetic field of the sun. Here I am, disrupting observations of the world’s most expensive telescope, to look at the sun through a 40 MILLIMETER lens. There’s a stunning reciprocity to it. This is the team of people that helped us learn so much about the cosmos: young solar systems, old galaxies, even the famous photo of the black hole, that was taken here. Now I have a chance to show them something they didn’t know about the sky. It’s very special.

We sit in a small waiting room lined with folding chairs, waiting for the blood pressure check. Staff go first, they need to get up the mountain as soon as possible. This is routine for them, they sign the waiver, sit down, still, give a perfect pulse, perfect heartrate. They stand up, roll their jacket back on, and move on. Now it’s our turn.

Maria Fernanda distributes paperwork. “This is the vision test”, she jokes. I look down at the paper. The text is minuscule. Here I must affirm that I do not have any of the following 35 pre-existing conditions. I strain to read them. A heroic effort was made to fit them all on one page. One by one, we pass around the clipboard and sign the waiver. Then the nurses take us in. Sitting in the chairs, everyone begins their personal relaxation ritual. Laura-May pulls up duo-lingo and sets it to math mode – solving simple problems like 9 x 7. Amy guides Fefo through a box-breathing exercise. She also tells me I shouldn’t sit with my legs crossed.

José comes out. He pauses at the doorway. He looks around at us, scared, disappointed. He heaves a heavy sigh. “I passed!” We roar with laughter. There’s no taking this man seriously. But some of us are not successful. Susan finds it hard to remain calm, and Fefo too. Though the nurses give them time to sit, time to drink water, they’re not able to pass their vitals. They won’t be going up the mountain today. They will have to try again tomorrow. This makes me nervous too – it’s not just a bureaucratic hurdle. I really could fail, too.

My turn. I walk in and sit on the chair next to the ECG. A young nurse slips the sensor over my thumb. There’s no way I’m passing this thing. I’m still riding the high from the solar observing. I can feel my pulse in my lips. Beep, beep, beep….. blood pressure … elevated but normal … heart rate … 110 … is that good? Don’t look at the screen, the nurse says. It makes people self conscious. “Take a few deep breaths…”

Pass.

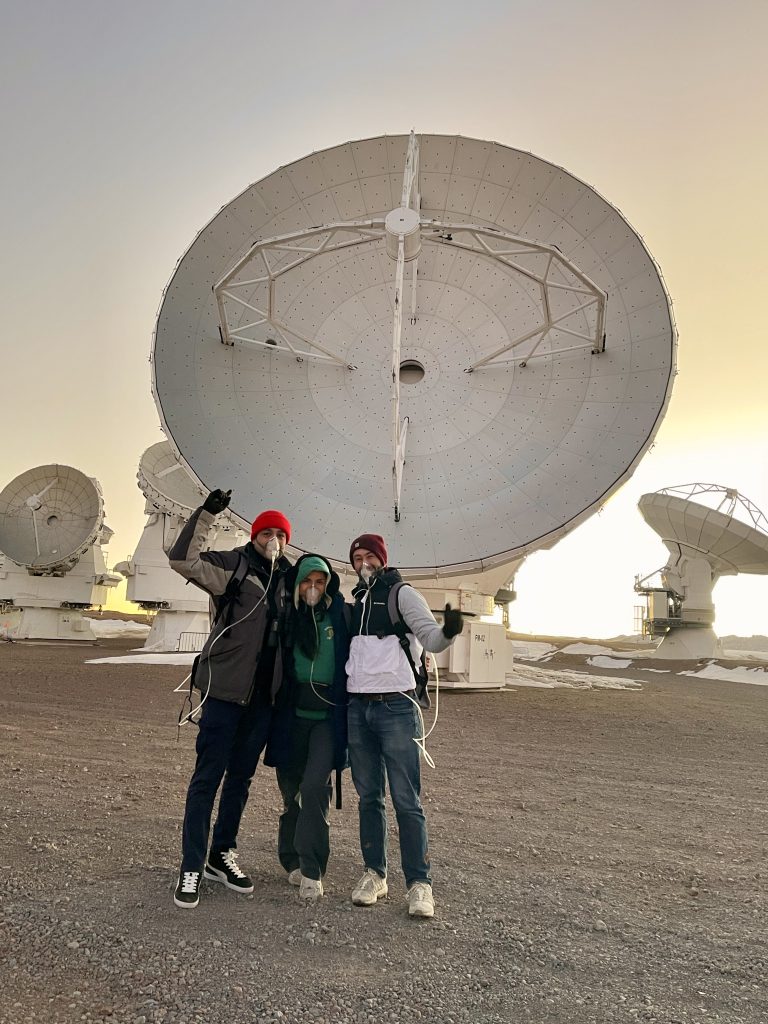

Now I join the others in the adjacent room. It’s a small open garage filled with green oxygen tanks. The tanks are filled in Calama city and freighted here. They even have to ship in fresh air. Maria Fernanda pulls a tank off a rack, screws on a pressure regulator, and then stuffs it in a backpack. She pairs this with a facemask, then hands the kits out one by one. We notice that staff aren’t wearing facemasks, they have a slim, sheik tube that delivers oxygen to their nostrils. Why is that? Visitors are mouth breathers. It takes conscious effort and practice to inhale through the nose. Inhaling through the mouth means the body doesn’t take as much of the oxygen that’s supplied. These facemasks are supposed to be foolproof. I stretch the elastic around my head, and then feel the plastic dig into my cheeks. We set our tanks to 0.5 liters/minute, the lowest setting. I sling the tank onto my back, holding my own backpack at my side. We jump into the two SUVs. They both have fresh car washes.

By the time we make the first turn up the access road, we’re looking down on the entire operations facility. The large building at the bottom of the slope is the site’s generator. It can burn natural gas or petroleum; they buy whatever’s cheaper.

Up and right we go, up the mountain road. Danilo fills out paperwork at the security checkpoint, and hands the guard our medical clearances. A donkey guards front of the door of the kiosk, docile, waiting for food. Now we begin our 30 km journey up the mountain.

“When was the first time you were here?”

“I was here 20 years ago. None of this was built yet. I was mountainclimbing with friends and we were lost. We were offroading on this exact peak. We were lost and the sun was setting. We eventually bumped into the Japanese astronomers over there — he pointed to another summit — and they helped us. It was totally wild the first time I was here. There was no road.”

Now that we are higher, we have in fact left the desert. The humidity level rises at these altitudes, so there is more greenery, shrubs, grass, and animals. At first, we see notice a coat of ice over the side of the road. Ascending, the pile of snow grows higher and higher. At first, sparse cacti poke out above the horizon. Extra wide tractors are still busy putting the finishing touches on the road clearance. Maintenance is constant. “What kind of music do astronomers listen to?”

“You know, it’s mostly metal, I don’t know if you noticed.” He clicks on his Stereo. A thrashing drum solo begins. Gravel snaps and crunches under the car’s wheels. I look out over the landscape. Electric guitar and polyrhythms suit it well. The slope is gradual – I can’t find the low site anymore. The Andes surround us on all sides. One has no sense of scale when they look toward the horizon. Those mountains are hundreds of kilometers away.

Danilo explains more about the Atacama’s geography. Astronomy is the United States’ #5 investment in Chile, but mining is #1. He explained how the operations threaten the ecology, especially the scarce but clean sources of water under the scorched soil. “When did the copper mining start?” “Ohh… about 3.000 years ago.” He referenced the indigeneous people, who have been metalworking for a very long time. “But the big mining started in 1918 when the Guggenheim group got the contract to build the telegraph lines for the US”.

Climbing further, there is now a rocky slope 4 meters high on the side of the road. On this stretch, they needed to blast their way through the mountainside to make room for the road. The car slows down. Look! On top of the slope, Vecuña! Pointy ears and black, spherical eyes, vecuña are the smallest species of camel. We roll down the window, aim binoculars and cameras at them, then continue up to the snowcapped peaks.

An industrial sized plow passes us the other way down the road.

At this point, I’ve said a few things that don’t make sense. “I think… I think my oxygen isn’t working. But you know… this is nice…” “Bill… what?” I turn the flow rate up and I suddenly feel better. Then, a tap on my shoulder. “Look right!” Across the plain, 50 or so satellite dishes. They’re in survival mode: tracking the sun to try to melt the snow.

Danilo stops the car, throws the parking gear up with crunch, and steps out.

We’ve reached the high site just in time for sunset. We walk inside – the nightshift is underway. The facility is buzzing with people and radio communications. We all begin to change into our extra layers. The temperature will plunge without the sun. A clinician makes her rounds; she administers one more oxygen test before we leave to walk the grounds.

I take a moment to explore the building. There is a canteen with a large window overlooking the facility. Golden sunlight pours in. There’s a radio comms room, a toilet, and, what’s this? A coffee machine?

Ignoring all the warnings, I press the button and brew an espresso. I’m grinning. I’m already up the mountain, there’s no more test to pass. I can indulge. “There’s even coffee up here!” “Yes, but it’s decaf”. Danilo grins back.

We zip up our coats and adjust our hats, and set our cameras atop their tripods. We walk out through the entryway, holding 2 sets of glass double doors for each other. Footsteps out onto the Marslike terrain. I’m still not used to sunsets from the mountaintop. There are extra colors that you don’t get to see from sea level. It’s unforgettable and indescribable. Cameras can’t capture the depthless gradient of these shades I’ve never seen before. Pink, orange, and blue are not so different from one another. You can’t put your finger on the point where the hue changes. The transition between them is uninterrupted by a single cloud. The mountains grow orange, minute, by minute. The satellite dishes slew, noiselessly atop the landscape. They’re totally silent when the move, and they’re controlled remotely so they move without warning. We’re instructed not to go closer than 10 meters. On this trip, I’m committed to using my eyes and living the experience. I leave responsibility for the excellent photos to the 8 others with cameras and experience. But now, I pull out my cell phone and take one very nice picture. The steel parabola slices the sunset gradient diagonally. I look at the photo. I’m satisfied and tell the others to try from my point of view.

I turn to face the north. Near to the horizon, peering out the distance, there is a sharp transition to a cobalt blue. Look at that extra color. “What causes that?” It’s the shadow of the Earth. Professional astronomers are used to mountaintops. This is only a new phenomenon for me. The shadow of the Earth? So it’s nighttime over there but not here? I still can’t explain it.

In the winter, near the equator, sunsets are short. After a short 20 minutes of pictures, stars emerge above in stampedes out of the darkness. I’m no longer too warm. The photographers are concentrated on their craft. I just look up, and around. Mark points out toward the horizon, where yellow-pink light still permeates. Mercury has made an appearance! Since Mercury is close to the sun, its never seen far above the horizon. You need a vantage point like this to see it.

The light dims. I now notice, at the rear of each dish is a green signal light, spinning, rotating around every 5 seconds or so. At first they give just a hint of green to the backside of the dishes. As the sky darkens, they come to dominate the scene. If you look at most photos of the ALMA site, people do their best to balance out the green in their editing, so everything ends up looking too orange, even the sky.

There’s a Japanese observatory still 600 meters above where we’re standing. When completed, it will be the highest in the world.

As the only one not taking photos, I’ve learned at this point how to avoid getting in anyone’s shot. Ask for permission before moving, proceed slowly, and try to stay behind where people are facing. I walk up to José as he’s tweaking his long exposures. We hang out in front of the tiny LCD screen. Then, I notice a streak of light slowly panning across the sky, headed for zenith. Could it be?

“Space station! Space station, space station!” I point to the sky and shout and repeat, as a child would. I’m the first one to catch it. “Really?” José asks. “I’m going to try to get in the shot.” I run up to the others, and a few start to chase it. The international space station orbits the earth 16 times per day, but it’s only overhead a specific location every few months. When it is, it will make multiple passes every 90 minutes for a few days. This pass seems to be directly overhead. It’s only 400 km above the earth – closer than Berlin is to Munich. It’s football field sized solar panels reflect sunlight, and it becomes the brightest object in the sky.

The space station. People live up there.

Back at José’s tripod, we talk more about seeing Andromeda back at Cerro Tololo. I feel the moisture on my face – the mask traps the moist air from my lungs. It’s not so comfortable, so I adjust it again. Then, the elastic cord unties and falls out of its loop. Oh, am I in trouble? José looks at me with concern. I try to tie the knot again and fail. I take off my gloves and try again. The cord slips through my hands. “Bill, you should go to the car.” I look across to the car. “There’s no time!” I push the mask to my face, take a few breaths, and then continue to work at the cord. Will I pass out if I don’t fix this?

It took me five attempts with the cord to realize that I’m not in any danger at all. The air is still flowing, if I hold the mask to my mouth with my hand, then I can breathe normally. This illustrates how poorly judgement and decision making goes with lower oxygen. The tanks only bring us back to the oxygen level found at the lowsite. I walked calmly to the car, and someone helped me tie the elastic again.

The night marches on, the hums of machinery and clicks of camera shutters. Moisés is astonished by the quality of the photos he can take just with his phone. He sets his it for a 10 second exposure, rests it face down on the hood of the car, and waits. When he lifts it back up, he can see the blue white core of the galaxy directly above us.

At midnight, our guide invites us to get back in the cars. 6,7,8, 9….. he counts us to make sure no one has walked off. The terrain is deceptive. Many have gotten injured with one harmless step. As we’re rounded up to get back in the cars, the photograhers stand out there until the last moment chasing the perfect shot. Finally, they throw their tripods on the trunk and pack in. We start down the mountain. José and I agree to meet in the lobby at 02:30 to look at Andromeda again. During the drive down, they pack their equipment. In the cradle like rocking of the bumpy road, we feel a true exhaustion.

Most photo credit goes to Moisés López Caeiro, an amazing science teacher from Spain! See you at the 2026 eclipse!