I bought it off Kleinanzeigen on a damp, foggy Berlin afternoon. It’s made of wood, manufactured by the company Berlebach during the East German era. A frowning man met me at the concrete entranceway, dressed in a work-from-home hoodie. He didn’t even step fully outside, but instead leaned impatiently halfway out the heavy blue door.

“Ich suche nach einem stabilen Stativ.” (I’m looking for a stable tripod.) Stabil is also German slang for something cool. I smile. The joke doesn’t land with him. “Well, do you want it?” “Can I give you 85 euro?” “The price is 90, do you want it or not?” I hand him 90 euros cash.

Berlebach was founded in 1898. They specialize in high-quality wooden photography equipment. Read the company history for yourself; it’s dripping with the geopolitics of two world wars, the rise and fall of communist East Germany.

I got home and started mixing and matching tripod heads with it. My ball head, my equatorial mount, none of them fit. Why couldn’t I get this to screw on? Then I realized. It’s because of geopolitics. You see – all camera equipment is built with a strange sort of a screw, the 1/4″ – 20. Yes, the quarter-inch screw, with 20 threads per inch. The only land still using inches on an industrial scale are the United States. The standard proliferated throughout the the world of photography because of the country’s mighty economy. It’s not the only example: your television is also measured in inches. But East Germany was an incredibly isolated regime, ideologically opposed to everything from the US and the Western Republic of Germany. Listening to western rock music was punished with prison time and only conducted in secrecy. Inside the Demokratische Deutsche Republik, you would never find a corrupt consumerist capitalist camera to mount on these old Berlebach tripods. Therefore atop of it you find a metric M6-1.0 thread. 6 millimeters diameter, with 1 winding per millimeter.

Side by side, the screws appear identical to the untrained eye. (When you’re screwed, you’re screwed) If you try to put things together though, all the material would strip out. The two systems are not compatible.

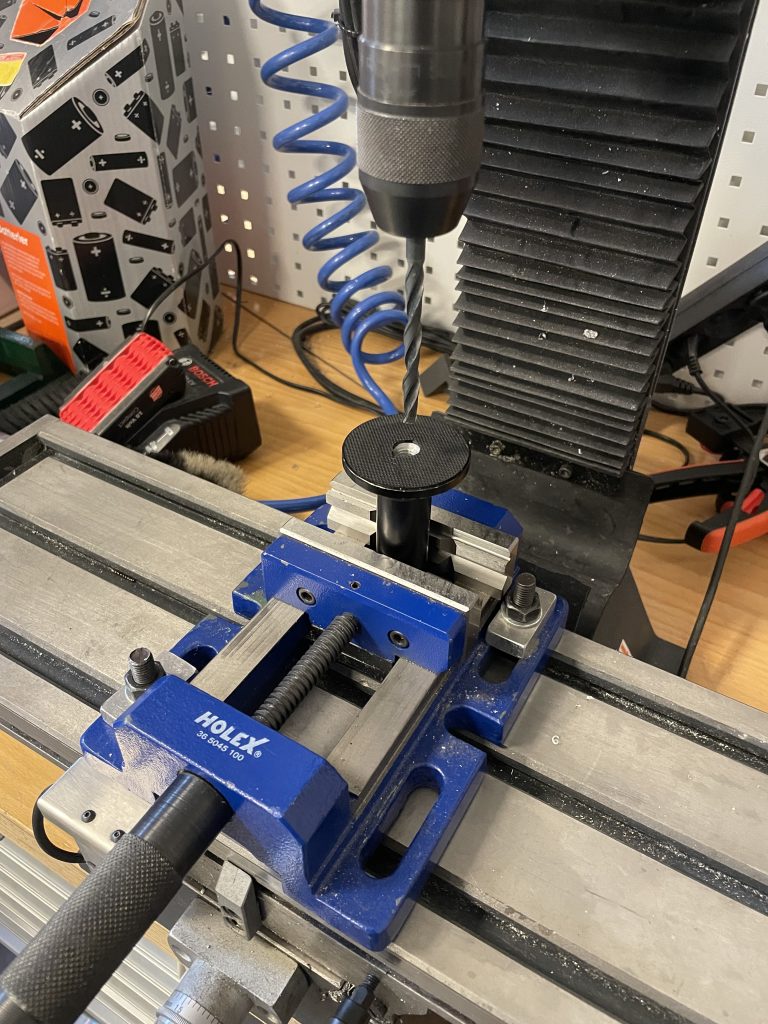

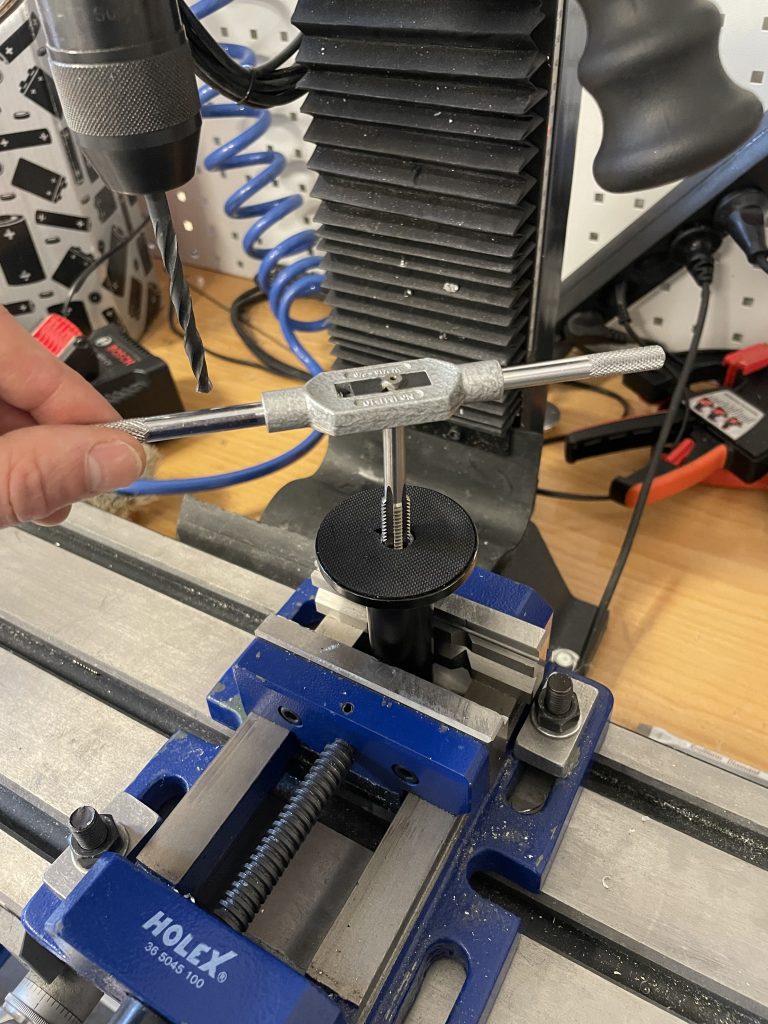

There is a solution. I could drill into the tripod, create a 3/8″ – 16 thread, then buy a 3/8″ – 16 adapter. A 1/4″ – 20 studded rod could then be screwed into that, and viola, I could then attach all possible tripod heads.

For this, you need a drill press and a screw tap to cut new windings into the hole. In Berlin, I didn’t have access to these tools. So I threw the tripod onto the pile of equipment that I might use some day. Then I moved the pile to Copenhagen, where it languished in my storage cellar while I settled into my new life. Germans have a word for this too: Im Keller verstauben.

But now I do have access to the right equipment. So I’ve picked the tripod up again, and drilled that thread.

The USA standard screw size, modified into the base of a tripod made in a country that doesn’t exist anymore. My telescope is manufactured in China, imported and doublechecked by Germans. I choose a Manfrotto ball head to aim my telescope – Italian design. It’s all fixed together by a single screw, manufactured in India to the “English Imperial” standard. We’re all connected, it seems.

Last night, out at Nørreport, I deployed this telescope to show Jupiter’s clouds to a man who was more curious than the average. He asked me how far away Jupiter is in light years, he asked me what the clouds are made of. Then he asked me where I’m from, because I’m obviously not from Denmark. “Jo jo, jeg kommer fra USA”. Then he started laughing and nodding his head. “I’m from Afghanistan.” Our whole conversation was in Danish.

Experiences like this convince me that the night belongs to everyone. It can’t be owned, and what we can see must be shared equally. We won’t let it be lost to pollution and politics. How strange it all is, that a man from the United States and a man from Afghanistan can come together in Denmark to look through a telescope whose providence is simply: Earth.